Note: this essay is cross-posted at Skepticality.

In my previous post about Shakespeare’s Beehive, the book in which antiquarian booksellers George Koppelman and Daniel Wechsler argue that they have found a dictionary owned and annotated by Shakespeare, I focused on some of the problems with the assumptions that underlie their arguments. In this post, I will examine the evidence that they present.

Their evidence is made up of correspondences or verbal parallels they see between the annotations and Shakespeare’s works. Many of these rely on what they call mute annotations: underlinings, slashes by major entries, circles by subsidiary entries. This is problematic for several reasons. For one thing, they can pick out any word or words from a flagged entry (whether underlined or not) to match with a passage in Shakespeare. Sometimes they pick words scattered in various distantly separated parts of the Alvearie that appear close together in Shakespeare.

I haven’t looked at every page of the Alvearie in detail, but I have browsed through it quite a bit. I have yet to see a single page that has no mute annotations. This seems to be a case where computational stylistics would be useful. It is not enough to say, “the annotator flags this word, and Shakespeare uses this word.” We need to know how many flagged words appear in Shakespeare, how many don’t, and how many appear in the works of Shakespeare’s contemporaries. Michael Witmore and Heather Wolfe of the Folger Shakespeare Library point out some of the questions that need to be answered:

2) Rare and peculiar words. How many of the words underlined or added in the margins of this copy of the Alvearie are used by Shakespeare and Shakespeare alone, as opposed to other early modern writers? Further, how many of the words that are not marked or underlined in this copy of Baret are nevertheless present in Shakespeare’s works? Are these proportions different, and to what degree?

3) Associations. K[oppelman] & W[echsler] write of “textual proximity in Baret mirroring textual proximity in Shakespeare” (107). As we know from studies of other resources used by early modern writers, it is in the nature of a dictionary to list commonly associated words (including synonyms and words that co-occur in proverbs or adages). How likely is it that Baret’s Alvearie–as opposed to proverbial wisdom and common association–is the only possible source for Shakespearean associations? Again, following the line of questioning above, how often do spatially proximate combinations of words that are not underlined in Baret nevertheless co-occur in Shakespeare’s works? How often do the proximate marked words in Baret occur near one another in writers other than Shakespeare?

Until the necessary statistical analysis is performed, we can only assess the strength of the parallels Koppelman and Wechsler offer as evidence.

They are weak. Incredibly weak. So weak that many do not deserve to be called verbal parallels at all.

And some of the parallels are indeed closer to writers other than Shakespeare. For instance, by “cawdle” (caudle, a spiced gruel mixed with wine or ale and used medicinally), the annotator adds, “a cawdle vide felon.” Under “felon,” Baret includes a figurative use of caudle: “with a cawdle of hempseede chopt halter wise, and so at the least to vomit them out, to cut them off from the quiet societie of Citizens, or honest Christians” (“cawdle” is underlined by the annotator). The annotator also adds a cross reference under “hemp:” “hempseed chopt halter vide felon.” Koppelman and Wechsler admit that Shakespeare never uses “felon” and “caudle” together, but note that Jack Cade uses both words in Act 4 of 2 Henry VI. In the second speech, Cade says, “Ye shall haue a hempen Caudle* then, & the help of a hatchet” (4.7.88, quoted from First Folio, which mistakenly prints “Candle”).

Koppelman and Wechsler quote the main definition of “caudle” from the Oxford English Dictionary (OED); however, they don’t note that definition b. specifically refers to a caudle made of hemp. Two passages are quoted, Cade’s speech and a passage from the Martin Marprelate tracts of 1588: “He hath prooued you to have deserued a cawdell of Hempseed, and a playster of neckweed.” This wording is closer to Baret than is Shakespeare’s, and it is earlier. Did the tract author own this copy of the Alvearie? I have no reason to think that he did. Did Shakespeare borrow from Baret or Marprelate? Or was a hempen caudle a well-known idea?

This supposed verbal parallel is actually stronger than many of the ones Koppelman and Wechsler note, and it more closely resembles someone else’s writing.

Another (comparatively) strong verbal echo appears in Richard III. The Duke of Clarence says he thought he saw “a thousand fearefull wracks” (First Quarto, 1.4.24). Among the horrors and treasures of those wracks, he saw “Wedges of gold” (1.4.26). The same phrase appears in Baret. As Koppelman and Wechsler note, “Twice the annotator’s eye and pen have fallen on the link between wedges and gold, as is demonstrated in the underlined text: wedges of gold – a precise recording of which we see in the extracted speech of the Duke of Clarence.”

This does seem like an unusual phrase, and the exact wording does appear in both Shakespeare and Baret, although the annotator only underlines the first word. However, the phrase was not unusual in the Renaissance. In the OED, definition 3a under “wedge” reads: “An ingot of gold, silver, etc.? Obs.” “Wedge” was first used to mean an ingot of metal in the Old English period. The phrase also appears in some early modern translations of the bible. In the Coverdale Bible (1535) and the Great Bible (1539), Job 28:16 contains the phrase, “No wedges of gold of Ophir,” while Joshua 7:21 of the Geneva Bible (1560) includes the phrase, “Two hundredth shekels of siluer and a wedge of gold of fyftie shekels weight.” Considering how common the phrase was, it seems rash to assume Shakespeare found the phrase in Baret.

The same is true of “yield the ghost,” uttered a few lines later, again by Clarence. This phrase is “printed in Baret with a simple slash and variant spelling addition provided by the annotator.” This again is quite a common phrase, a variant of “give up the ghost.” The earliest quotation in the OED comes from the late 13th-century South English Legendary. It is also used in the last verse of Genesis (49:33) in the King James Bible.

In discussing Hamlet, Koppelman and Wechsler say, “Baret receives a citation in many critical editions of Hamlet for the peculiar use of ‘stithy.'” To indicate the “many” critical editions that refer to Baret, they cite one edition from 1819 (Thomas Caldecott, ed., Hamlet and As You Like It: A Specimen of a New Edition of Shakespeare, London: John Murray). They fail to explain what is “peculiar” about Shakespeare’s use of the word. Although it may be unfamiliar to many people today, it was common enough in Shakespeare’s day. Shakespeare’s use is slightly unusual in that he uses it to mean forge or smithy rather than an anvil. The OED includes only five quotations for this usage. Shakespeare’s is the earliest. Baret, however, defines “stithy” as “anvil.” The annotator adds “enclume,” French for anvil. In other words, if Shakespeare’s use of the word is peculiar, he did not get that association from Baret, and the annotator didn’t record the meaning Shakespeare uses.

In discussing Shakespeare’s love of unusual words, Koppelman and Wechsler mention “cudgel:”

[In Baret, a]t B98, bang or beate with a cudgell, the annotator underlines cudgell and puts a slash in the margin next to bang. Shakespeare was the first to use cudgel as a verb (the noun existed, in archaic forms, since the ninth century of earlier). Cudgel in 1 Henry IV has the literal meaning “to beat with a cudgel,” but in Hamlet it takes the figurative meaning of “racking one’s brain”: “Cudgell thy braines no more about it.”

This might be significant if Baret or the annotator mirrored Shakespeare’s unusual use of the word, but they don’t: neither uses it as a verb, and neither uses it figuratively. Instead, Baret uses and the annotator underlines a rather ordinary word used in a rather ordinary way (and cudgel, though it has a long history, was not “archaic” in Shakespeare’s day).

In their discussion of the sonnets, Koppelman and Wechsler mention what they think “may elicit the biggest ‘wow’ of all.” The annotator has marked the following entry with a circle: “Let, impediment: hinderaunce.” No words are underlined. We are supposed to be amazed by the similarity to the opening of Sonnet 116: “Let me not to the marriage of true minds / Admit impediments….” The problem is, of course, that Shakespeare’s “let” and Baret’s “let” have quite different meanings and functions. Baret’s “let” is a noun. It means impediment. He is defining it as an impediment. The OED defines it in a similar manner. Shakespeare uses the verb, meaning “to allow.” When Shakespeare was composing his sonnet, did he perhaps consider the other meaning of “let”? Was he playing with that meaning? I don’t know. It’s possible, but if he did, there is no reason to think he took the association from Baret. The two words are synonyms. Shakespeare didn’t have to read Baret to know that.

Koppelman and Wechsler believe that the best evidence that Shakespeare was the annotator comes from the trailing blank, a blank page at the end of the book on which the annotator has written extensively, mostly English words with French equivalents. They believe this page relates to the Falstaff plays (1 & 2 Henry IV, Merry Wives of Windsor and Henry V, in which Falstaff’s death is announced and in which Shakespeare includes a significant amount of rudimentary French). They claim that almost all of the (English) words appear in one of these three plays. Not all appear exactly, however. For instance, the annotator has included “pallecotte,” which he defines as “habillement de femme.” Shakespeare does not use the word “pallecotte,” but he does use “coat” and “woman’s gown.” These do not seem extraordinary matches.

There is one phrase that is a truly extraordinary match to something Shakespeare-adjacent. The annotator writes “A lowse un pou lou lou.” This exact phrase appears in an 1827 French translation of Merry Wives.” That is an interesting coincidence, but Koppelman and Wechsler see great significance in it. I don’t understand how a French translator working long after the deaths of Shakespeare and the annotator can have any bearing on the relationship between the two.

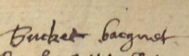

Of another word pair, Koppelman and Wechsler say, “Bucke looks to have a hyphen mark at the end of the annotation, connecting it to bacquet (basket), turning it into bucke-bacquet. Buck-basket is used four times, all in Merry Wives, including a pair of usages by Falstaff.” Buck-basket is an unusual word: the OED lists only one usage in addition to Merry Wives. However, when I look at the word pair, I don’t see “bucke-bacquet,” I see “bucket bacquet.”

According to the OED, the etymology of “bucket” is uncertain, but it apparently comes from “Old French buket washing tub, milk-pail (Godefroy s.v. buquet).” The Online Etymology Dictionary says “bucket” comes from Anglo-Norman “buquet.” In other words, I suspect this is an English word with its French equivalent. Such word pairings make up the bulk of the page. Koppelman and Wechsler have transformed a glossary-style entry into a bilingual compound word with strong Shakespearean associations. This seems a particularly egregious example of confirmation bias. They concluded long ago that Shakespeare was the annotator, and then they settled down to find evidence. This is not the way one discovers the truth.

It is, I suppose, possible that Shakespeare is the annotator, but until a rigorous analysis (including statistical analysis) is done of the text, all we can say is that Koppelman and Wechsler have provided very weak evidence for their hypothesis.

ES

[…] – Shakespeare’s Beehive. – Review of Shakespeare’s Beehive, Part 1 – Review of Shakespeare’s Beehive, Part 2 – Skeptical […]

Referring to your mention of Joshua 7:21 in the Geneva Bible (1560) and in the Bee Hive:

Two facts are generally accepted, one that the Geneva Bible was the main biblical source for Shakespeare; and two, that the Geneva Bible (1568? edition) was Edward de Vere’s personal bible, wherein he habitually placed marginalia as does the owner of the Bee HIve.

As Shakespeare was familiar with the Geneva Bible, and de Vere was, so was this mystery annotator of the Bee HIve. Determining the hand-writing and manicule-style may be the path to the owner–or user–of the dictionary. Probably not de Vere’s script but possibly someone in his playwrighting corps.

Finding the author provenance of “Baret” is another useful direction. It happened more than once that the works of de Vere ended up in print under the names of his disciples, friends, relatives, or associates, usually with the dedication to him. Here Sir Thomas Smith and Laurence Nowell are prominently mentioned in the front matter. They were de Vere’s tutors. Burghley the dedicatee was his warder and later father-in-law. de Vere himself was declared by Ronsard as L’auteur de la Lyre, the Begetter of Poetry.

The dictionary appears to be an attempt to expand the Elizabethan English vocabulary, drawing from modern and ancient language sources.

Such a project would have to have been a corporate effort, suited to the guild structure of master and apprentices of the time, rather than an individual achievement. Perhaps part of a larger attempt to seriously advance what later became the English Renaissance.

William Ray

wjray.net

Regarding “wedge(s) of gold” in Baret and the Geneva Bible: I don’t think this tells us anything about the identity of the annotator. The phrase was common, going back centuries before Baret, Shakespeare and the annotator. The same phrase appears in the Great Bible as well (in Job).

According to Koppelman and Wechsler (who admittedly aren’t entirely reliable) whenever the annotator quotes the bible in English, his phrasing is always closest to the Great Bible or the Bishops’ Bible. He does not use the Geneva Bible. Koppelman and Wechsler say this fact helps to establish the approximate date of the annotations because “[a]fter the composition of Henry V, Shakespeare’s biblical allusions turn sharply to the Geneva Bible, but before 1600 the echoes are notably not from the Geneva translation.” It is clear here once again that they are assuming Shakespeare is the annotator rather than objectively considering the evidence, since their statements only relate to Shakespeare’s use of the Geneva.

Eve noted: “According to Koppelman and Wechsler (who admittedly aren’t entirely reliable) whenever the annotator quotes the bible in English, his phrasing is always closest to the Great Bible or the Bishops’ Bible. He does not use the Geneva Bible. Koppelman and Wechsler say this fact helps to establish the approximate date of the annotations because ‘[a]fter the composition of Henry V, Shakespeare’s biblical allusions turn sharply to the Geneva Bible, but before 1600 the echoes are notably not from the Geneva translation.'”

But according to Dr. Naseeb Shaheen {*Biblical References in Shakespeare’s Plays* 1999, 2011, pp. 38-39):

“The vast majority of Shakespeare’s biblical references cannot be traced to any one version, since the many Tudor Bibles are often too similar to be differentiated. But of the more than 1,040 biblical references that are listed in this volume (excluding some 120 references to the Psalms…), there are approximately 80 instances in which Shakespeare is closer to one version, or to several related versions, than to others.

So less than 8% of the biblical references in Shax can be traced to one version (or several related versions).

Shaheen p. 44: “[A]lthough the Geneva Bible may have been the version that Shakespeare knew best and which he seems to refer to most often, the influence of other versions is clearly evident, and no one version can be called ‘Shakespeare’s Bible.’”

So how can K&W claim to date the annotations when they don’t even know the basics? And really?? Shakespeare was the only person who could have annotated a dictionary? Agree they are not interested in reviewing the evidence on its own accord but are shoe-horning such to fit their own self-serving fantasies.

Aside from their too confident conclusions about when Shakespeare used which bible, that quote about dating also strikes me as an example of circular reasoning: they are supposed to be determining whether Shakespeare is the annotator, but here–quite early in the book–they are assuming he is the annotator. Using the Geneva Bible as dating evidence only works if Shakespeare is the annotator (assuming for a moment that there aren’t other problems with that statement).

[…] Skeptical Humanities: Review of Shakespeare’s Beehive, Part 2 https://skepticalhumanities.com/2014/04/28/review-of-shakespeares-beehive-part-2/ […]